6 Torsion

Moments can produce multiple effects on a body or structure, depending on the axes around which they act. Whereas later sections of the text discuss the effect of moments that cause bending are discussed (see Chapter 7, Chapter 9, Chapter 10, and Chapter 11), this chapter concerns the effects of moments that cause torsion.

Torsion occurs when a moment is applied around the longitudinal axis of a body. This type of moment is known as torque and the effect of torsion is a twisting action. Torsion is found in many common situations. Some examples of applications in which torsion is a primary form of loading include these:

In machinery, rotating shafts, such as transmission shafts that transmit power, are subjected to torque.

When one uses a wrench to tighten or loosen a bolt, the bolt is subjected to torque.

Hinge pins are subjected to torque when the rotating elements they are attached to (e.g., doors) are rotated.

Vertical poles from which road signs and traffic lights are mounted are subjected to torque when forces are applied to the horizontal elements of the structure. For example, in Figure 6.1 wind force applied to the horizontal poles or traffic lights causes the vertical pole to twist around the vertical axis.

Note that in this particular example the vertical pole would also be subject to bending (from moments around the cross-sectional axes of the pole). Problems in which this type of combined torsion and bending effects occur are discussed in Chapter 14.

This chapter focuses on the effects of pure torsion (no axial or bending loads) on bodies.

Section 6.1 describes the general effects of torsion. Section 6.2 details the process to determine internal torques as a preliminary step to stress and deformation calculations. Section 6.3 and Section 6.4 offer derivation equations for calculating the stress and deformation caused by torsional loads. Section 6.5 examines how these concepts can be applied to solving statically indeterminate torsion problems, which is a similar process as axial loading statically indeterminate problems described in Section 5.5. Finally, Section 6.6 considers how the concept of torque applies in power transmission applications.

6.1 The Effect of Torsion

Click to expand

As mentioned, a torsional moment causes the body to twist, and this action results in shear stress.

Consider the pleated tube shown in Figure 6.2. Figure 6.2 (A) shows the tube in an unloaded state with some of the pleats colored for identification. Figure 6.2 (B) shows that after a torque is applied, the pleats move vertically but not horizontally. We can say that all points remain in their original plane even as they twist to new locations around the perimeter of the cross-section. In other words, the shape of the cross-section is unchanged despite the twisting action.

.png)

Now consider the I-beam subjected to torsion in Figure 6.3. In this case the shape of the cross-section changes and the points do not remain in the same vertical plane (there is horizontal displacement as well as vertical). This shape change is referred to as warping. In this text we consider only circular cross-sections with no warping.

Returning to Figure 6.2, let’s consider the shape formed by the nondisplaced colored lines in Figure 6.2 (A) versus the displaced lines in Figure 6.2 (B). These images are shown again in Figure 6.4. In the nondisplaced case, a rectangle can be drawn around the green lines on the left with 90° corners. In the displaced case, the corners are no longer at 90°. From Section 3.4 we know that this change in angle is the definition of shear strain. The evidence of shear strain indicates that the applied torque results in shear stress.

6.2 Determination of Internal Torques

Click to expand

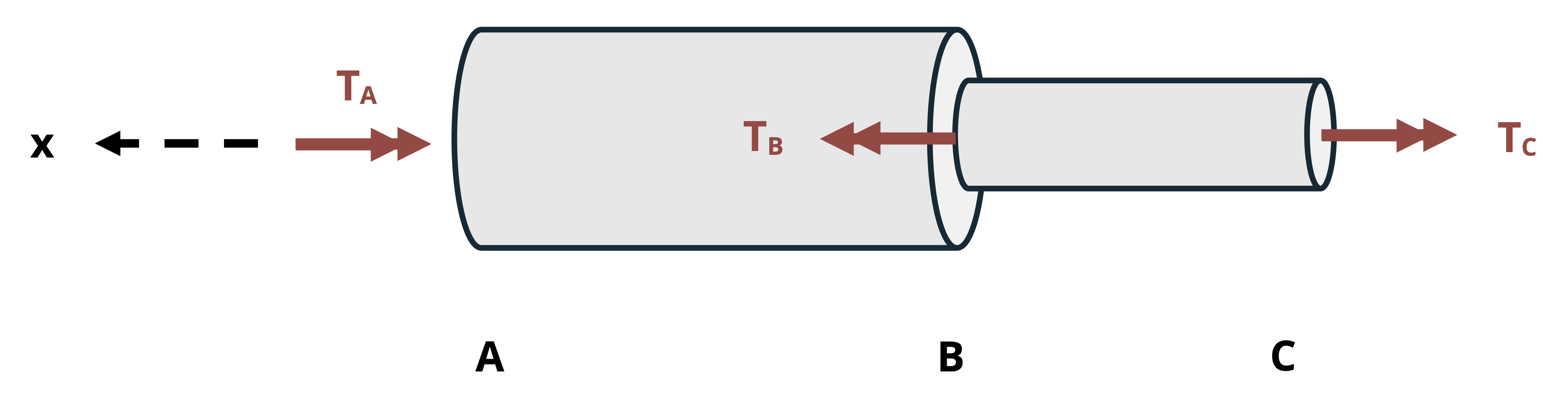

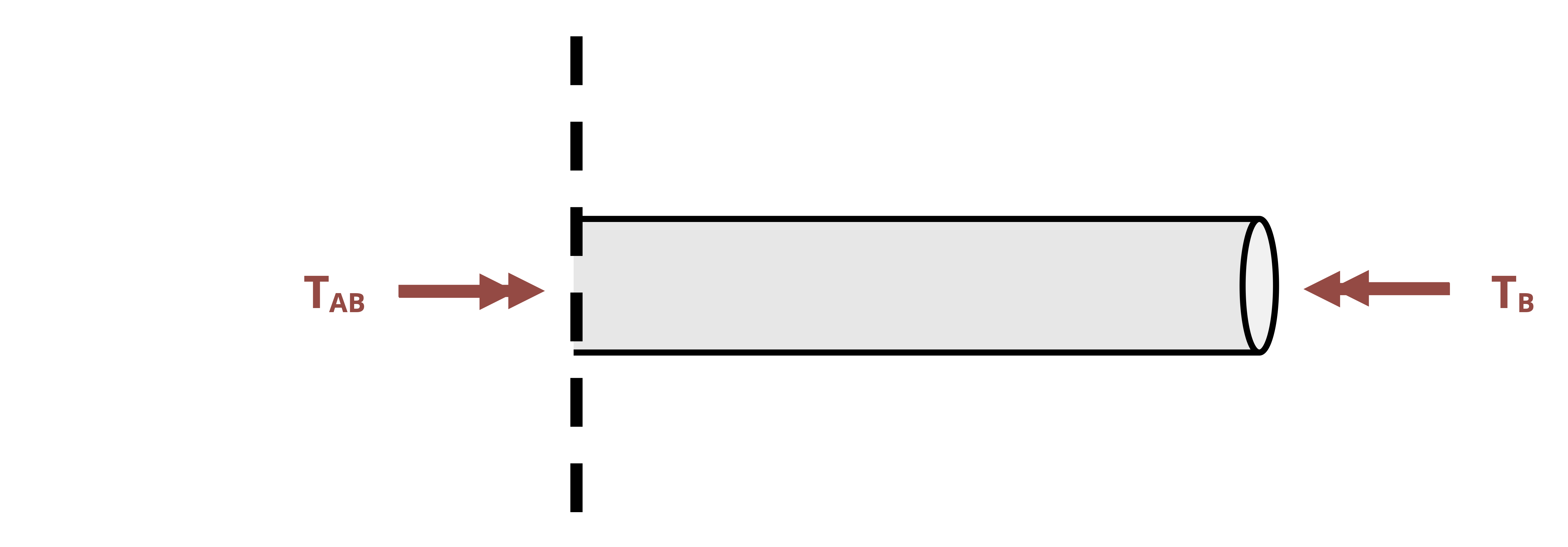

As with axial loading, stress and deformations from torsion vary from point to point within a body and are dependent on the internal torques at the individual points and on the geometric section properties. Internal torques can be found by sectioning bodies and applying equilibrium equations, just as we did when finding internal forces in axial loading problems (see Example 1.5, Example 2.1, and Example 2.2). In the case of internal torques, moment equilibrium around the longitudinal axis is applied instead of force summation.

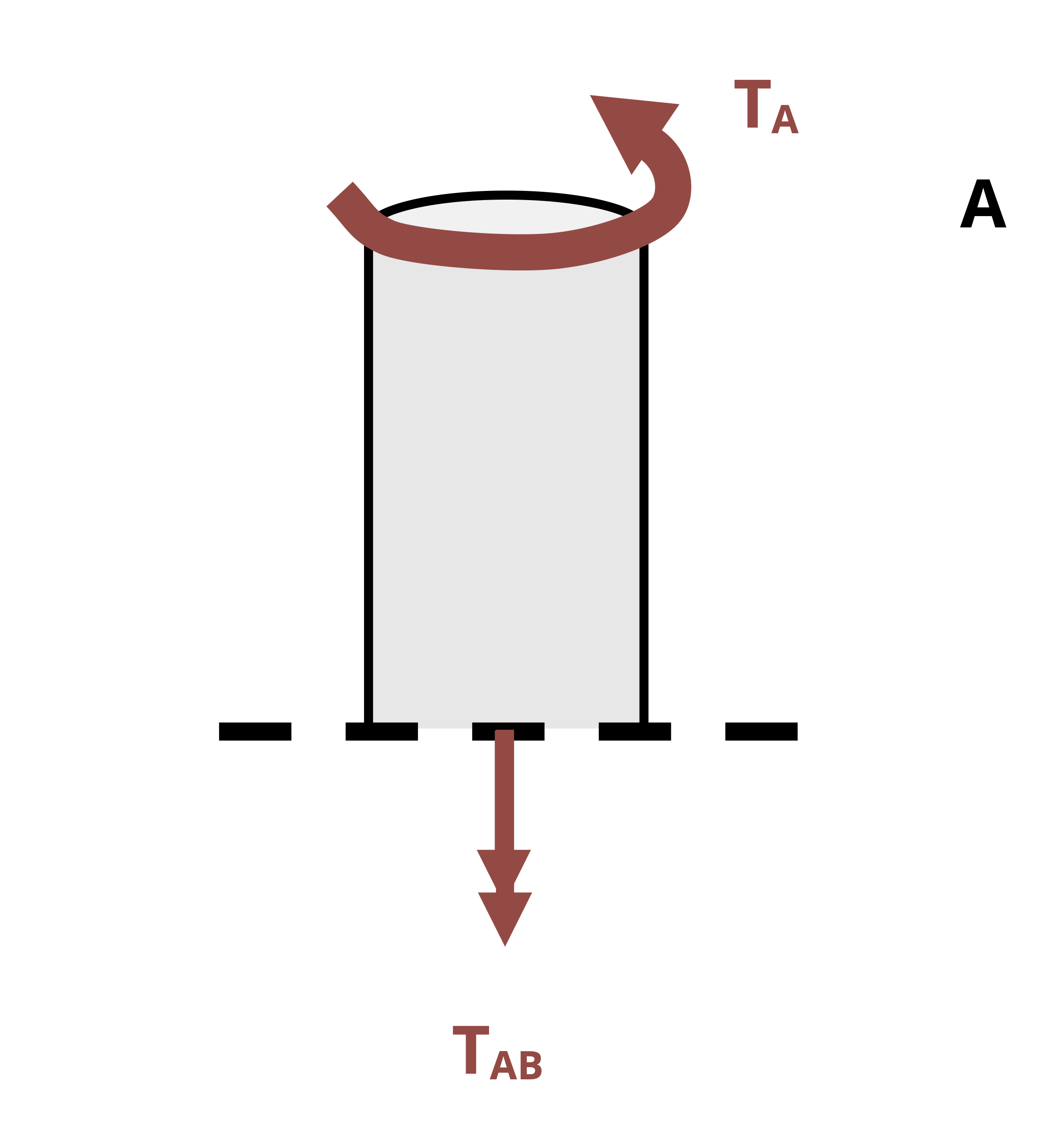

Before we examine the process of finding internal torque reactions, it would be beneficial to establish the sign convention and ways of representing torque used in this text.

6.2.1 Sign Conventions and Representation of Torque

In this text counterclockwise torques are considered positive and clockwise torques negative. However, the apparent direction of a torque depends on the perspective from which the rotation is observed. In Figure 6.5, the applied torque would appear clockwise if viewed from the left end of the bar toward the right and counterclockwise if viewed from the right end of the bar toward the left. As long as you are consistent, which perspective is used isn’t usually important. However, a typical convention (and the one followed in this text) is to look from the free end of the shaft (if there is one) toward the fixed end, or from the positive end of the longitudinal toward the negative.

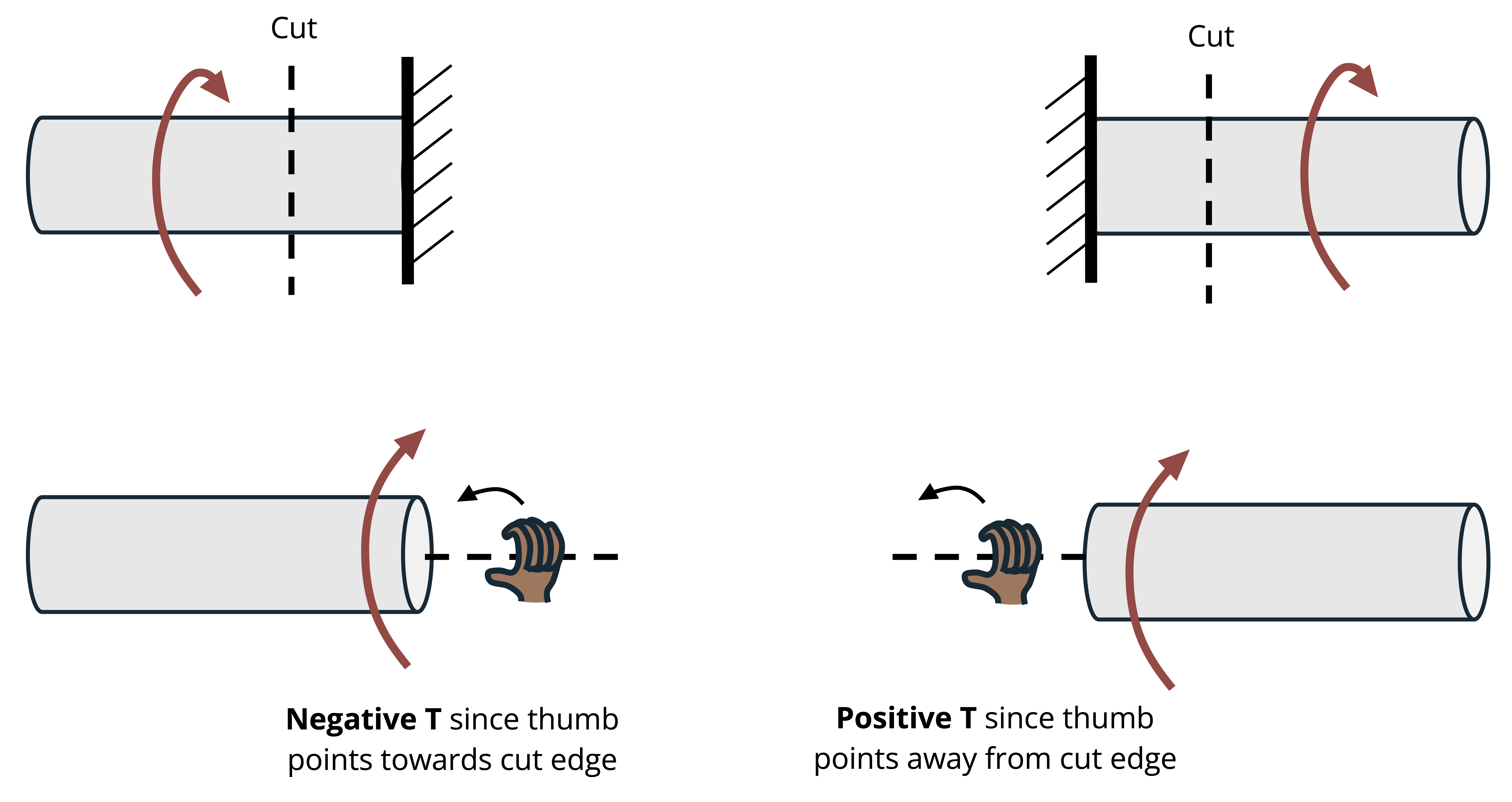

To visually determine whether a torque appears clockwise or counterclockwise can sometimes be difficult, so one helpful tool that can be used is the right-hand rule: Curl the fingers of your right hand in the direction of the rotation represented by the torque arrow. If in doing this your thumb points in the direction of the positive axis (the x-axis in Figure 6.6), a positive torque is indicated, and if it points away, a negative torque.

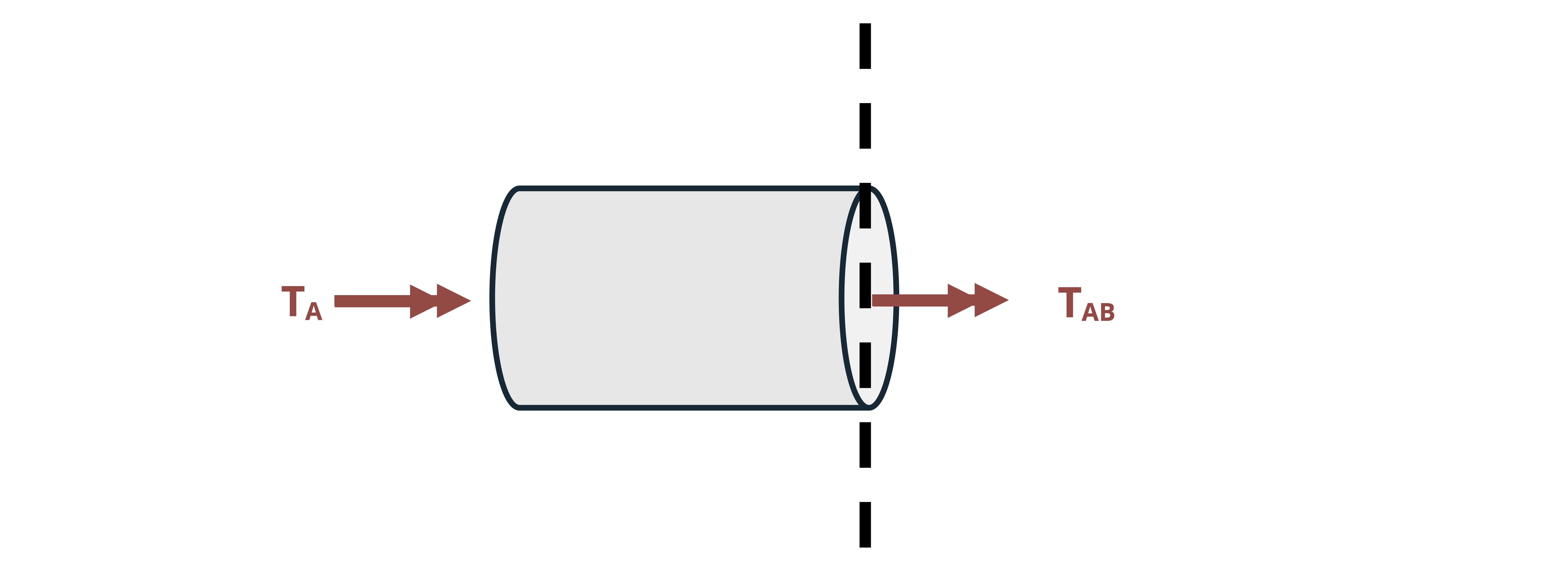

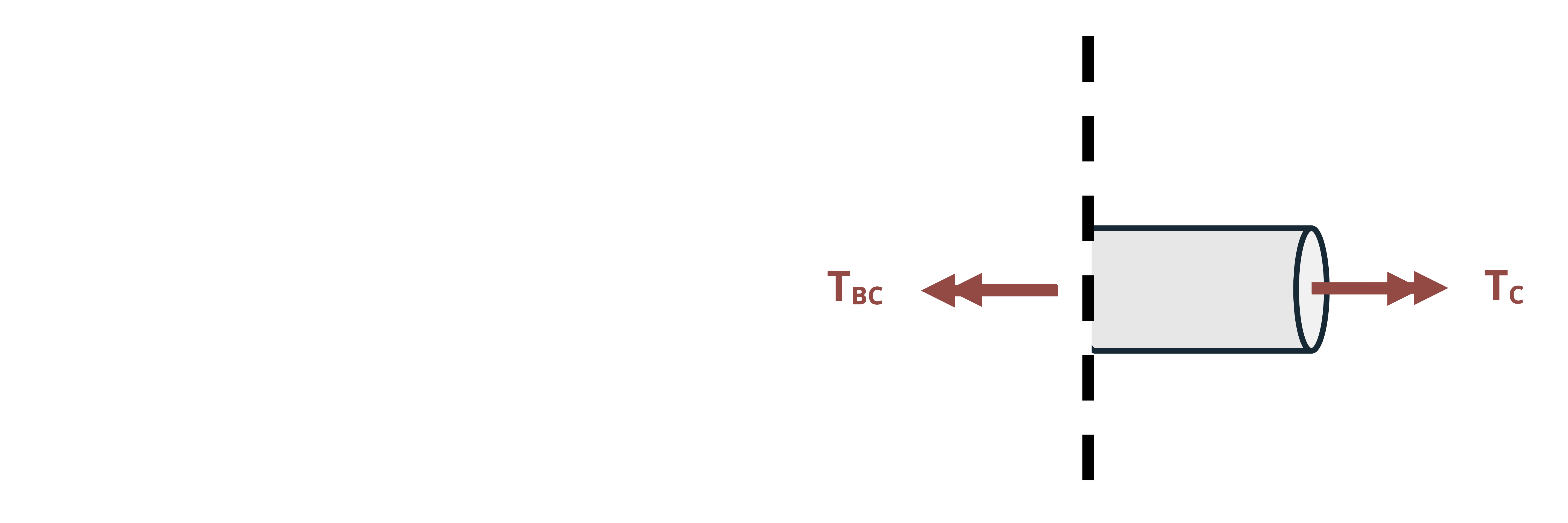

For bodies that are sectioned to find internal torques, consider the direction of the torsional moment from the perspective of looking from the cut edge towards the other end of the cut section. Imagine your right hand to be at the cut edge and curling your fingers in the direction of the torque. If your thumb points away from the cut edge, the internal torque is positive, and if your thumb points toward the cut edge, the internal torque is negative. This is illustrated in Figure 6.7.

Finally, since circular arrows can be difficult to draw in a way that clearly conveys direction, double-headed line arrows are frequently used to represent torque. Note that conventions can vary between texts and other sources. This text uses the following convention:

- On a whole body FBD used to determine external reactions, arrows facing in the direction of the positive longitudinal axis indicate positive torques (counterclockwise) and those facing the opposite direction negative torques.

- When applying equilibrium, the positive or negative sign from step 1 is used.

- For FBDs of cut sections used to determine internal torques, positive torques are indicated by arrows pointed away from the section’s cut edge, and negative torques by arrows pointed toward the cut edge. However, when summing moments, the regular convention of adding right arrows and subtracting left arrows will be used.

The direction of the internal torque is unimportant in calculating shear stress (the sign on the stress requires concepts discussed in Chapter 12) but is important when calculating angle of twist, as evident in Section 6.2.

Example 6.1 demonstrates how to determine internal torques in a multisection body as well as how to apply the described sign conventions.

6.3 Calculation of Shear Stress Due to Pure Torsion

Click to expand

This section explains the derivation of the shear stress equation that results from torsion of a circular shaft. Understanding the derivation lends clarity to the inputs of the equation and the assumptions necessary for use. If you wish to skip the derivation, go directly to Equation 6.1.

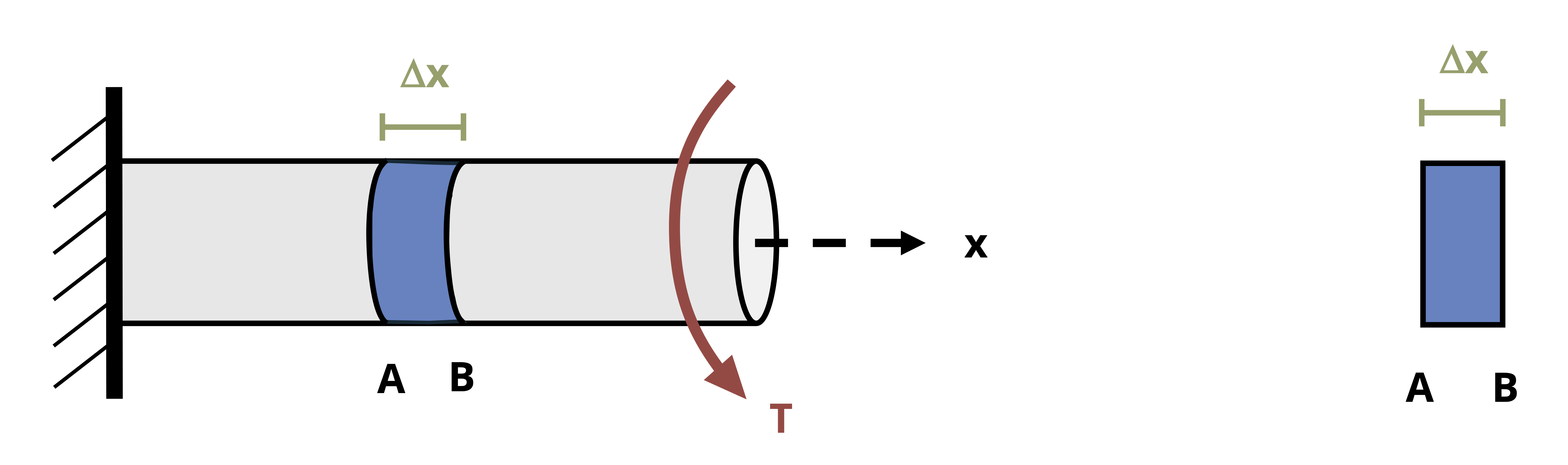

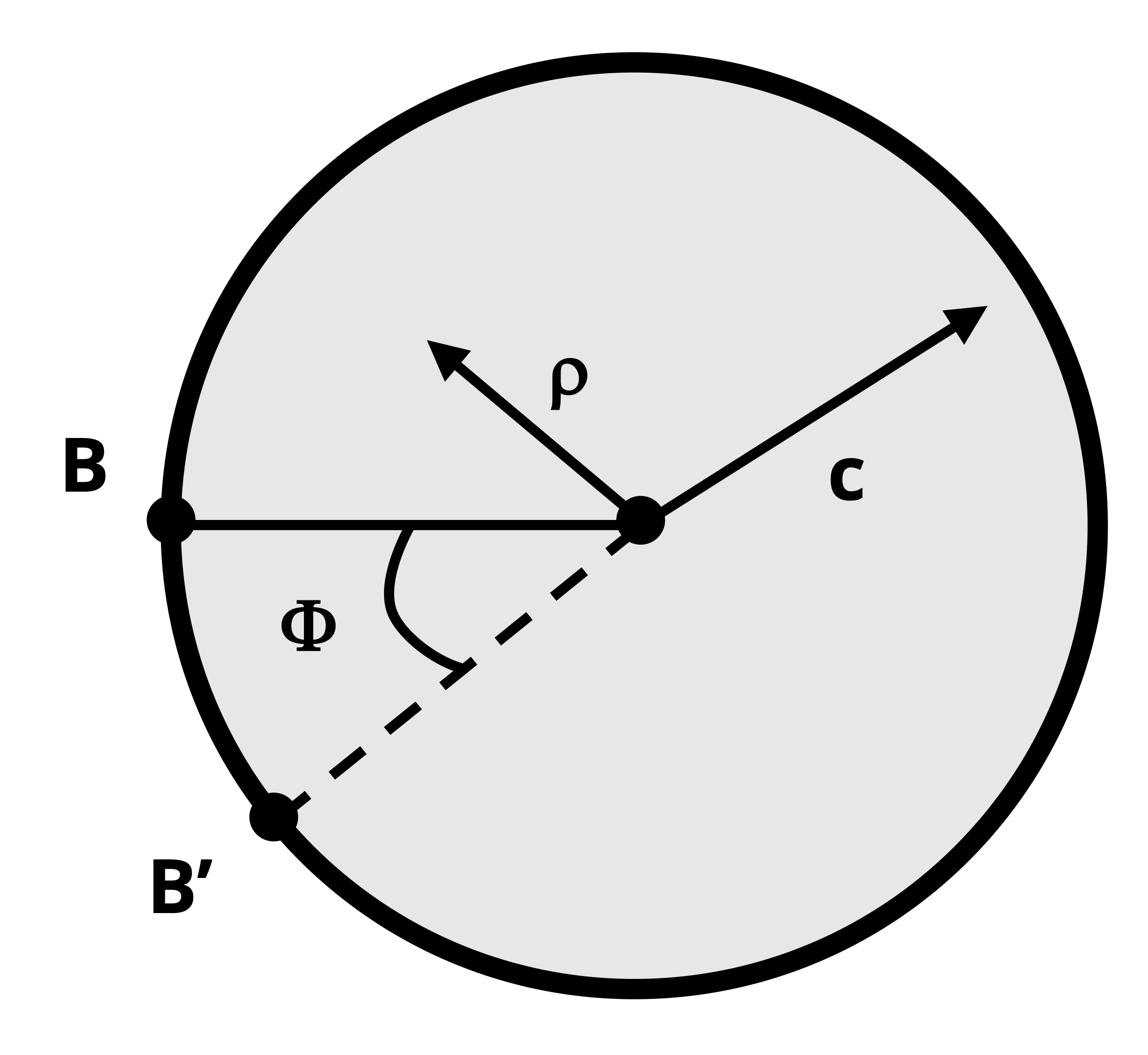

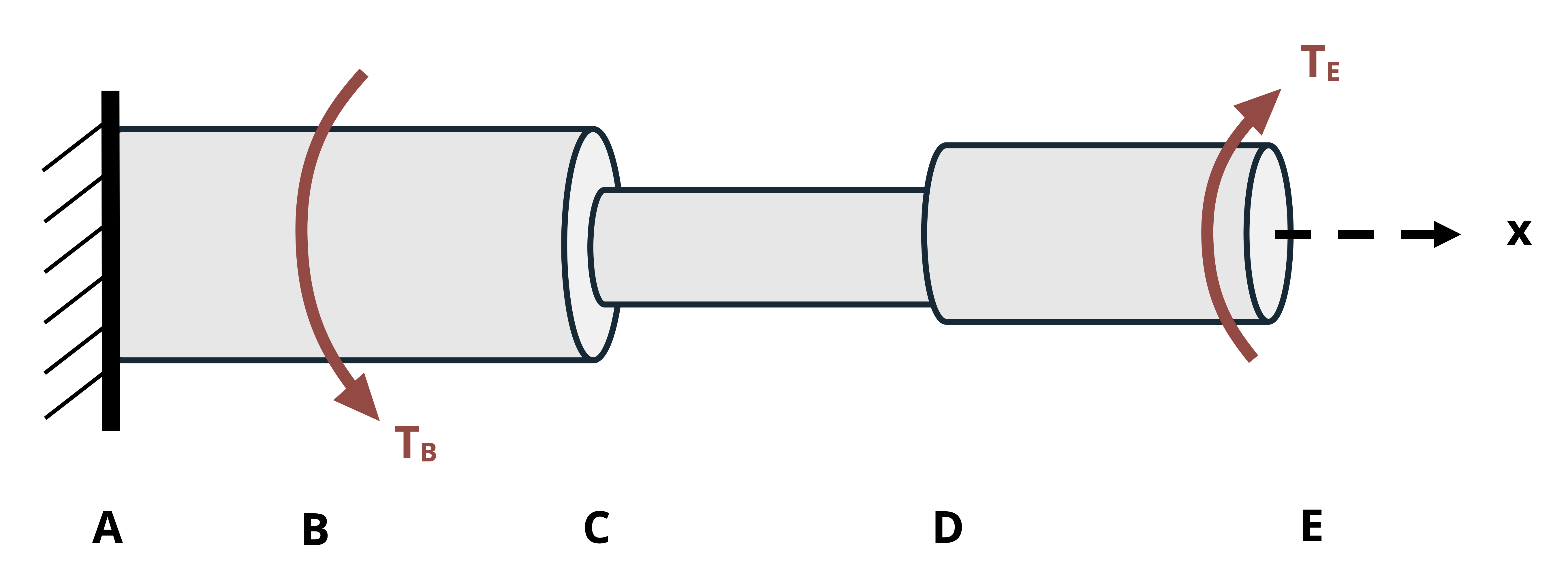

Consider a circular shaft fixed on one end and subjected to torque on the free end, as shown in Figure 6.8. The shaft has an outer radius, c, as shown in Figure 6.9 (B). For the given loading, the internal torque at any x location along the length of the shaft would also be T. We will examine a small sliver of the shaft, marked as AB.

Before the torque is applied, a horizontal line segment drawn across AB has a length of Δx. Now let’s consider the same shaft segment after the torque has been applied and points A and B move to A’ and B’ respectively. We can approximate that A’B’ is linear for a very narrow section of shaft (infinitely small Δx). An illustration of the resulting geometry can be seen in Figure 6.9 (A). Since the shaft is fixed on the left end, point B on the shaft will rotate more than point A. Point A’’ represents the relative location of A’ on the cross-section of B and B’.

Recalling that shear strain is the change in angle between two lines that are originally perpendicular, we can see that the angle of tilt of A’B’ relative to the horizontal line A’A” is the shear strain, 𝛾, that results from the torque. For an infinitely small Δx, the arc segment from A” to B’ can be approximated as vertical so that the shear strain 𝛾 can be expressed using trigonometry.

\[ \tan (\gamma)=\frac{A^{\prime\prime} B^{\prime}}{\Delta x} \]

The small-angle approximation (given an infinitely small Δx) results in

\[ \tan(\gamma)\approx\gamma=\frac{A^{\prime\prime} B^{\prime}}{\Delta x} \]

Now consider the cross-section of the shaft where points B and B’ are located, shown in Figure 6.9 (B). The angle between the radial lines leading from the center to points A” and B’ respectively is the shaft segment’s angle of twist. Since we are examining a very small section of the shaft, the angle is represented as Δφ (as opposed to the absolute angle of twist, φ, as measured from the fixed end). If the shaft’s outer radius is r = c, then the length of A”B’ is given by the arc length, so

\[ \mathrm{A}^{\prime\prime}\mathrm{B}^{\prime}=\mathrm{c}(\Delta \phi) \]

and

\[ \gamma=\frac{c(\Delta \phi)}{\Delta x}\text{.} \]

Generalizing this result for any point on the cross-section that is located at an arbitrary radial distance ρ from the center yields

\[ \gamma=\frac{\rho(\Delta \phi)}{\Delta x}\text{.} \]

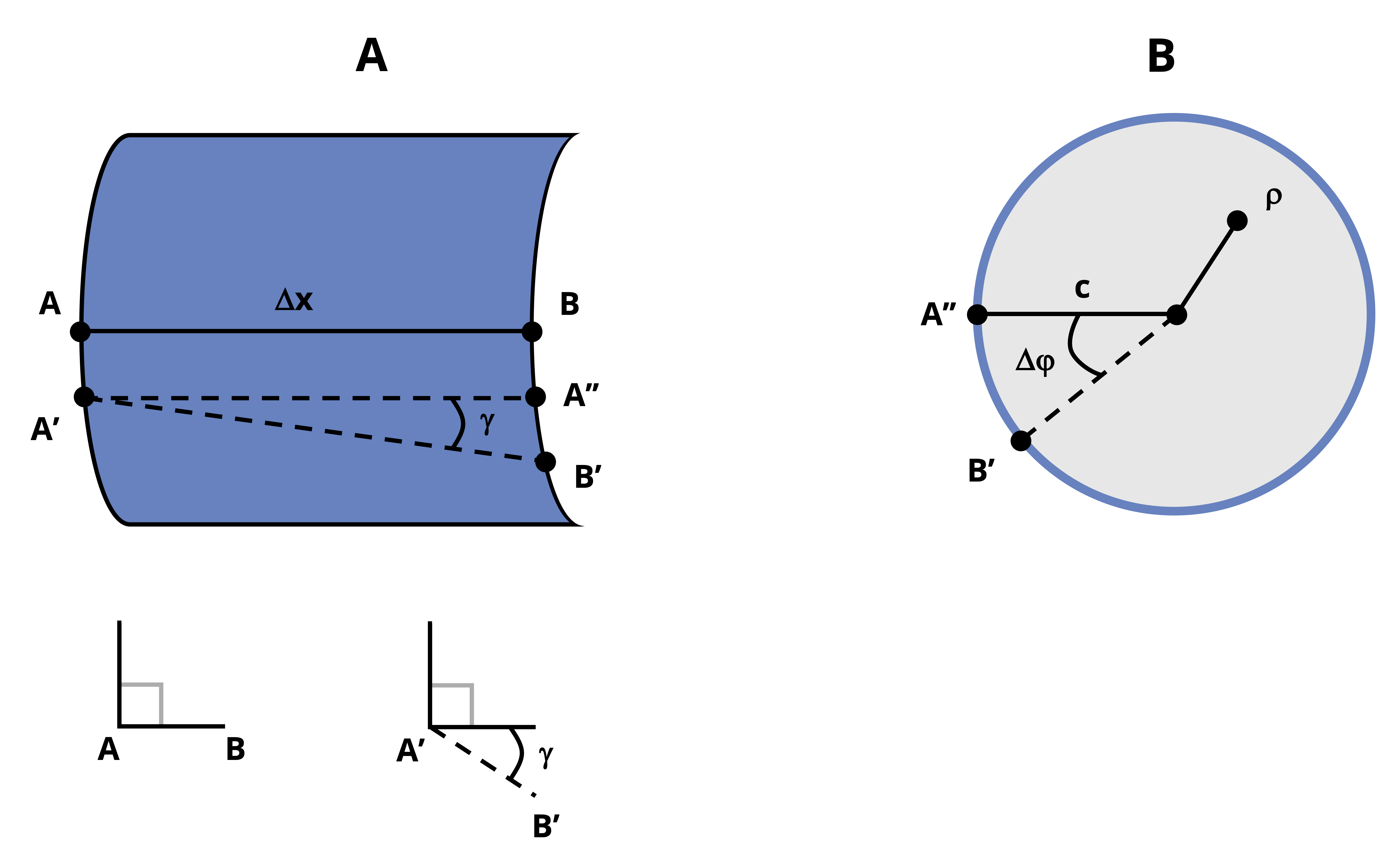

The resulting expression of γ shows that the shear strain varies linearly with ρ from the center of the cross-section to the outer radius, as illustrated in Figure 6.10. The shear strain is 0 at the center, and the maximum shear strain occurs at the max value of ρ which is ρ = c.

\[ \gamma_{\max }=\frac{c(\Delta \phi)}{\Delta x} \]

Substituting the general and max expressions for shear strain into Hooke’s law for shear stress, τ = G𝛾, reveals that shear stress also varies linearly from 0 to τmax in going from the center of the cross-section to the outer radius.

\[ \tau=G \gamma=G \frac{\rho(\Delta \phi)}{\Delta x}\\[10pt] \tau_{\max }=G \frac{c(\Delta \phi)}{\Delta x} \]

Figure 6.10 shows that the slope of the linear variation is \(\frac{\tau_{\max }}{c}\) and that the shear stress can also be expressed as

\[ \tau=\frac{\tau_{\max }}{c} \rho\text{.} \]

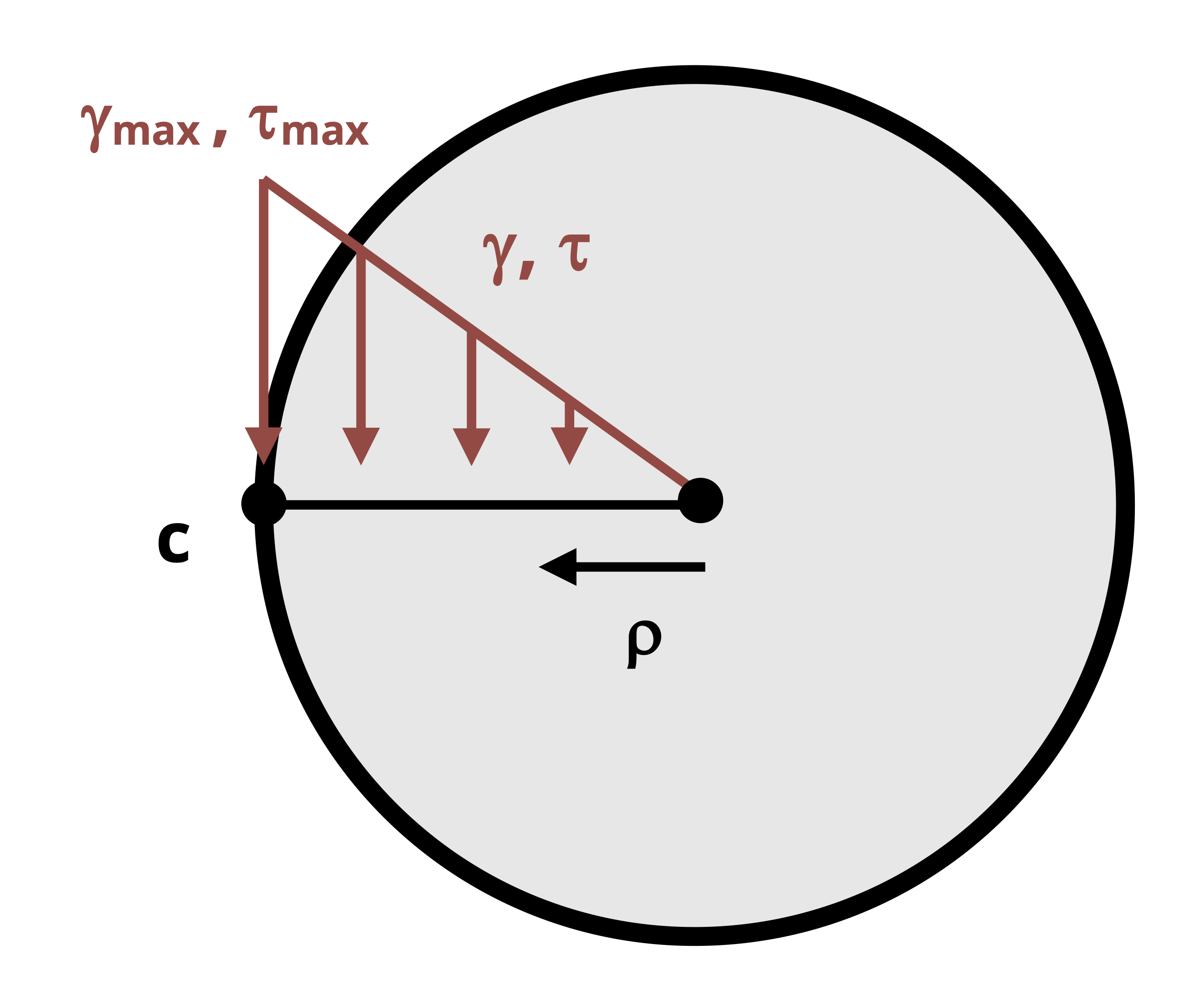

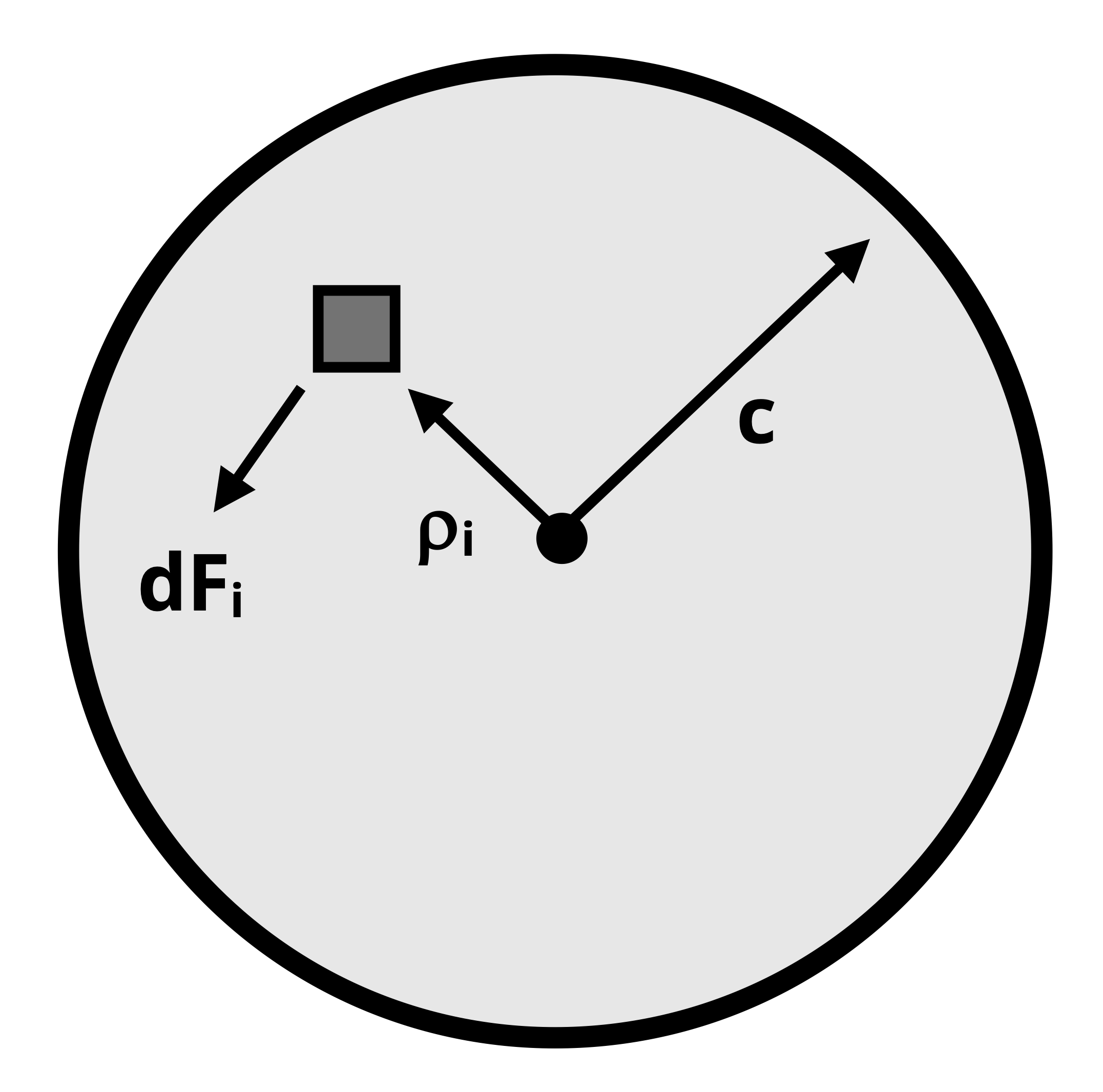

The last step in developing the shear stress relationship to torque involves considering the shaft’s equilibrium. Refer to Figure 6.11, in which the square is a representative point (i) subjected to an infinitesimal force dFi corresponding to the shear stress discussed above. If each point (i) on the cross-section has an area of dAi then dFi can be calculated as

\[ \mathrm{dF}_i=\tau_i \mathrm{dA}_i=\frac{\tau_{\max }}{c} \rho_i d A_i\text{.} \]

Recalling that the internal torque everywhere on the shaft is T, note that equilibrium dictates that the sum of the moments about the center of the cross-section should be equal to T. For an infinite number of points on the cross-section, this summation can be performed as an integral.

\[ \sum M_{center} =T=\int (d F_i) \ (\rho_i)=\int \frac{\tau_{\max }}{c} \rho_i^2 d A \]

Since τmax and c are constant, they can be pulled outside the integral, leaving the integral portion to be \(\int \rho_i^2 d A\), which is the definition of the polar second moment of area (also known as moment of inertia and area moment of inertia). This is the moment of inertia around the out-of-plane axis, which is the x-axis in this case. The polar second moment of area is denoted with the letter J in this text.

For a solid circular cross-section of outer radius r and outer diameter d:

\[ J_{solid}=\frac{\pi}{2} r^4=\frac{\pi}{32} d^4\text{.} \]

For a tube or hollow circular cross-section with outer radius and diameter ro and do respectively and inner radius and diameter ri and di respectively:

\[ J_{hollow}=\frac{\pi}{2}\left(r_o^4-r_i^4\right)=\frac{\pi}{32}\left(d_o^4-d_i^4\right)\text{.} \]

Replacing \(J=\int \rho^2_idA\) in our previous equation results in

\[ T=\frac{\tau_{\max } J}{c}\text{.} \]

This can be rearranged to

\[ \tau_{\max }=\frac{T c}{J}\text{.} \]

This equation yields the maximum stress on a given circular cross-section, which will occur on the outer edge of the shaft (where ρ = c). A more general form of the equation that can be used to find the stress at any point on the cross-section is

\[ \boxed{\tau=\frac{T \rho}{J}}\text{ ,} \tag{6.1}\]

𝜏 = Shear stress due to torsion [Pa, psi]

T = Internal torque [N·m, lb·in.]

𝜌 = Radial distance from center of cross-section to point of interest on the cross-section [m, in.]

J = Polar second moment of area [m4, in.4]

Here linear elastic behavior and small deformations of a circular cross-section have been assumed.

Note that for now only the magnitude of the shear stress (without sign) will be determined, since the sign for shear stress is not based purely on the sign of the torque. The sign on shear stress is discussed in Chapter 12.

Example 6.2 demonstrates the use of the above equations to determine shear stress in the same circular bar assembly used in Example 6.1.

6.4 Calculation of Angle of Twist

Click to expand

The deformation of a shaft that arises from applying torsion—assuming deformation is restricted to elastic deformation—is quantified by the angle of twist, φ. As discussed in Section 6.3 and illustrated here again in Figure 6.12, the angle of twist is the angle formed between the radial lines that correspond to the original location of a point on the cross-section and the location it moves to as a result of applied torque. The equation to determine angle of twist at various points along the shaft follows. If you wish to skip the derivation, go directly to Equation 6.2.

Recall from Section 6.3 that the shear strain can be expressed as \(\gamma=\frac{\rho(\Delta \phi)}{\Delta x}\). Also recall that Δx represents the length of a small section of shaft and Δφ is the change in angle of twist that occurs across that length. For an infinitely small section of shaft, the shear strain equation can be expressed in terms of differentials: \(\gamma=\frac{\rho(d \phi)}{d x}\).

Applying Hooke’s law (τ = G𝛾) and the equation for shear stress (Equation 6.1) yields

\[ \frac{\rho(d \phi)}{d x}=\frac{\tau}{G}=\frac{T \rho}{J G}\text{.} \]

Solving for dφ yields

\[ d \phi=\frac{T d x}{J G}\text{.} \]

Integrating both sides of the equation gives the total angle of twist for an entire shaft or section of shaft.

\[ \phi=\int \frac{T d x}{J G} \]

For a section (i) of shaft of length Li for which torque (Ti), material (Gi), and geometry (Ji), stay constant, this becomes

\[\phi_i=\frac{T_i L_i}{J_i G_i}\text{.} \]

For multisection bodies where each individual section has constant T, J, and G, the integral can be expressed in the form of a sum where the angle of twist of each distinct section is calculated individually and then all are added together.

\[ \boxed{\phi=\sum\phi_i=\sum \frac{T_i L_i}{J_i G_i}}\text{ ,} \tag{6.2}\]

𝜙 = Angle of twist [rad]

T = Internal torque [N·m, lb·in.]

L = Length [m, in.]

J = Polar moment of inertia [m4, in.4]

G = Shear modulus [Pa, psi]

In these calculations the sign of internal torque is important as it indicates the direction of the twist. If a section twists in one direction and the adjoining section twists in the opposite direction, the angles will subtract from each other, resulting in a smaller overall angle of twist. If, however, two adjoining sections twist in the same direction, the effect will be additive. According to the assumed sign convention discussed in Section 6.2, an overall positive angle of twist indicates that the shaft twists counterclockwise when looking from the positive end of the longitudinal axis to the negative and clockwise when looking from the negative to the positive end.

6.4.1 Units

If values for T, L, J, and G are used in Equation 6.2 such that the units are all consistent with each other, the overall unit works out to be unitless, as is expected for an angle calculation. Since the calculation is for an angle, the actual unit is in radians. To obtain an answer in degrees, convert the result of the equation by multiplying it by \(\frac{180^\circ}{\pi}\).

Because the angle of twist often works out to be very small, you may want to express the value in terms of μrad, which is 10-6 radians. To convert from rad to μrad, multiply the number of radians by 106.

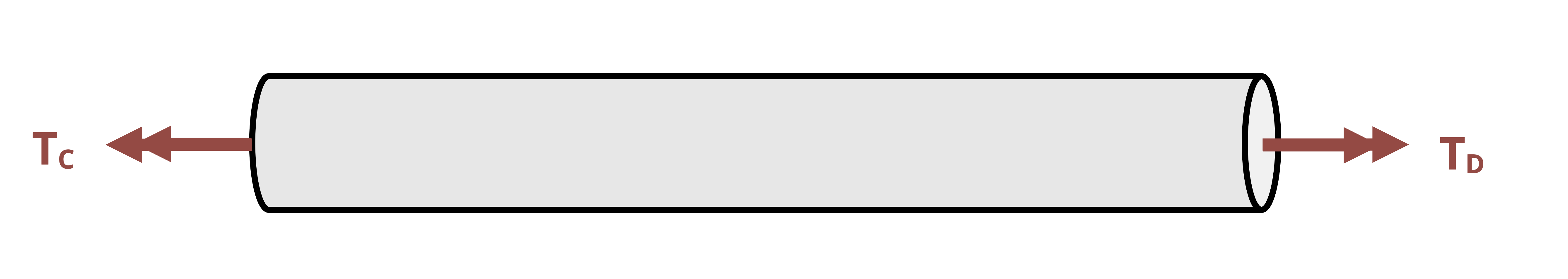

6.4.2 Notation and Relative Angle of Twist

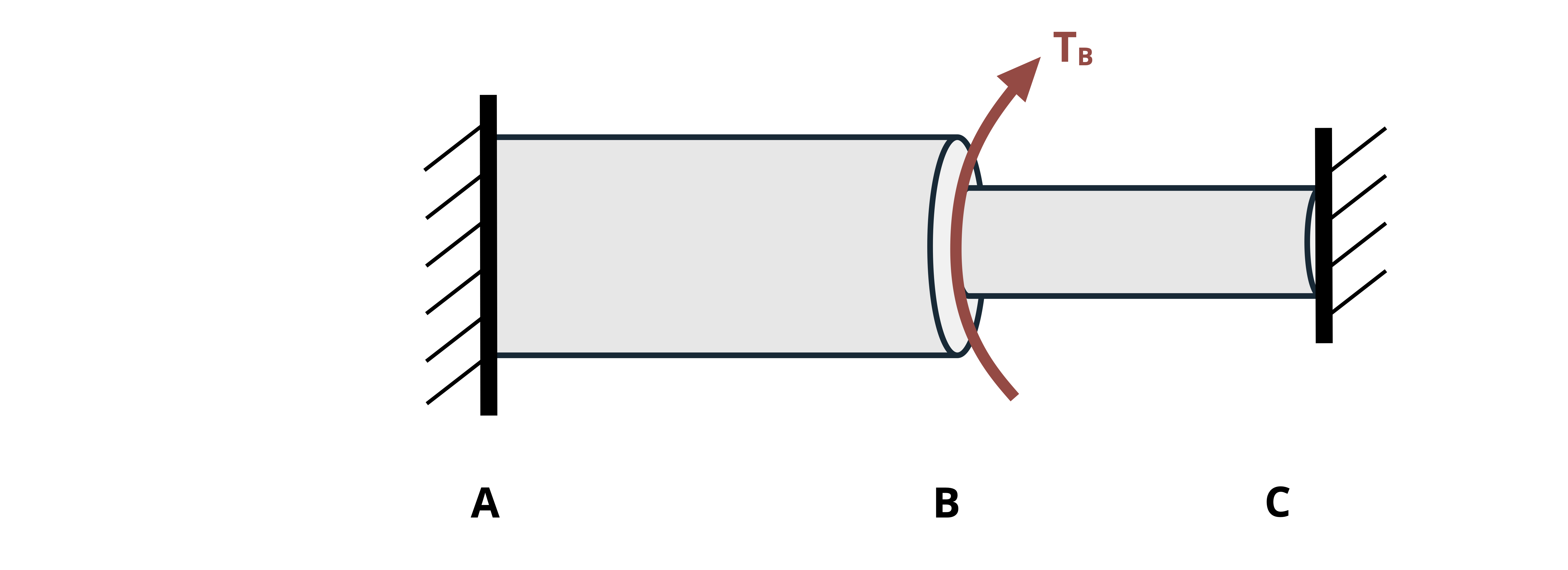

When finding the angle of twist, the angle at any given point along the length of the shaft relative to some reference point. Often the reference point is a fixed point (e.g., at a fixed support), so the relative angle is an absolute angle. In this case, the symbol φ is subscripted with the point along the shaft where the angle was calculated. For example, given the shaft assembly in Figure 6.13, the notation φB denotes the angle of twist at point B relative to the fixed point A.

When finding the relative angle of twist between two nonfixed points on the same shaft section (same T, J, and G), we notate the angle of one point relative to another on the same section by using two subscripts specifying the two points. For example, the angle of twist of D relative to C in Figure 6.13 is notated as φCD. In this case we perform the calculation for the angle of twist at D as if point C is fixed.

\[ \phi_{C D}=\frac{T_{C D} L_{C D}}{J_{C D} G_{C D}} \]

To find the relative angle of twist between two nonfixed points (let’s say B and D in Figure 6.13) that are on different shaft sections (i.e., one or more sections change between them due to changing T, J, or G), sum the angles of twist of each section between them. In this case, the notation would be φD/B, which is the angle of twist of D relative to B. If point C is where the section change occurs, the calculation would be

\[ \phi_{D / B}=\phi_{B C}+\phi_{C D}\text{.} \]

These concepts are illustrated in Example 6.3, which continues with the same bar assembly and loading used in Example 6.1 and Example 6.2.

6.5 Statically Indeterminate Torsion

Click to expand

As discussed in Section 5.5 for axial loading, we may sometimes encounter loading and constraint conditions that are statically indeterminate. In these situations, though a structure may be in static equilibrium, equilibrium equations do not provide enough equations to solve for all the unknown reactions. In many cases, the known constraints on deformation can be used to provide the additional necessary equations. Let’s consider the following two types of statically indeterminate problems for torsional loading:

Redundant supports: These are cases where each end has a fixed support. In this configuration, the shaft is constrained on both ends such that the overall angle of twist must be 0 if both ends are truly fixed. As a variation, we could also consider the case where the angle of twist is limited to a specified amount if there is a fixed degree of freedom on one end (for example if one side involves a loose connection).

Example 6.4 demonstrates how to solve a statically indeterminate torsion problem that falls into this category. The example considers both the case where the total angle of twist is 0 and the case where there is a fixed degree of freedom.

Example 6.5 re-examines part (a) of Example 6.4 to demonstrate a different method of solving the problem. This method is known as the method of superposition and is outlined below.

Coaxial or parallel shafts: Multiple shafts are bonded concentrically (one within another) so that they are constrained to twist as a unit by the same amount. In this case, the extra equation needed in addition to equilibrium comes from setting each shaft’s angle of twist equal to the other’s.

Example 6.6 demonstrates how to solve a statically indeterminate torsion problem that falls into this category of loading.

6.5.1 Method of Superposition

For the case of redundant supports, an alternative is to use the method of superposition. The method of superposition is based on the idea that the effects of individual loads on the deformation of a body can be calculated individually and then added together to obtain the total effect. To apply this method do the following:

- Draw the FBD of the whole body and write out the relevant equilibrium equations.

- Choose one of the supports to consider redundant, remove the corresponding reaction torque, and find the total angle of twist from the remaining loads.

- Put the reaction torque from the redundant support back, remove the applied loads, and then find the total angle of twist due to the replaced reaction torque in terms of the corresponding variable.

- Sum the angle of twist from step 2 and step 4 and set the total equal to zero (or a given angle as appropriate).

- Solve the equation resulting from step 4 for the reaction at the redundant support and then use the whole body equilibrium to solve for the reaction at the other support(s).

Example 6.5 demonstrates the use of superposition to solve part (a) of Example 6.4.

6.6 Power Transmission

Click to expand

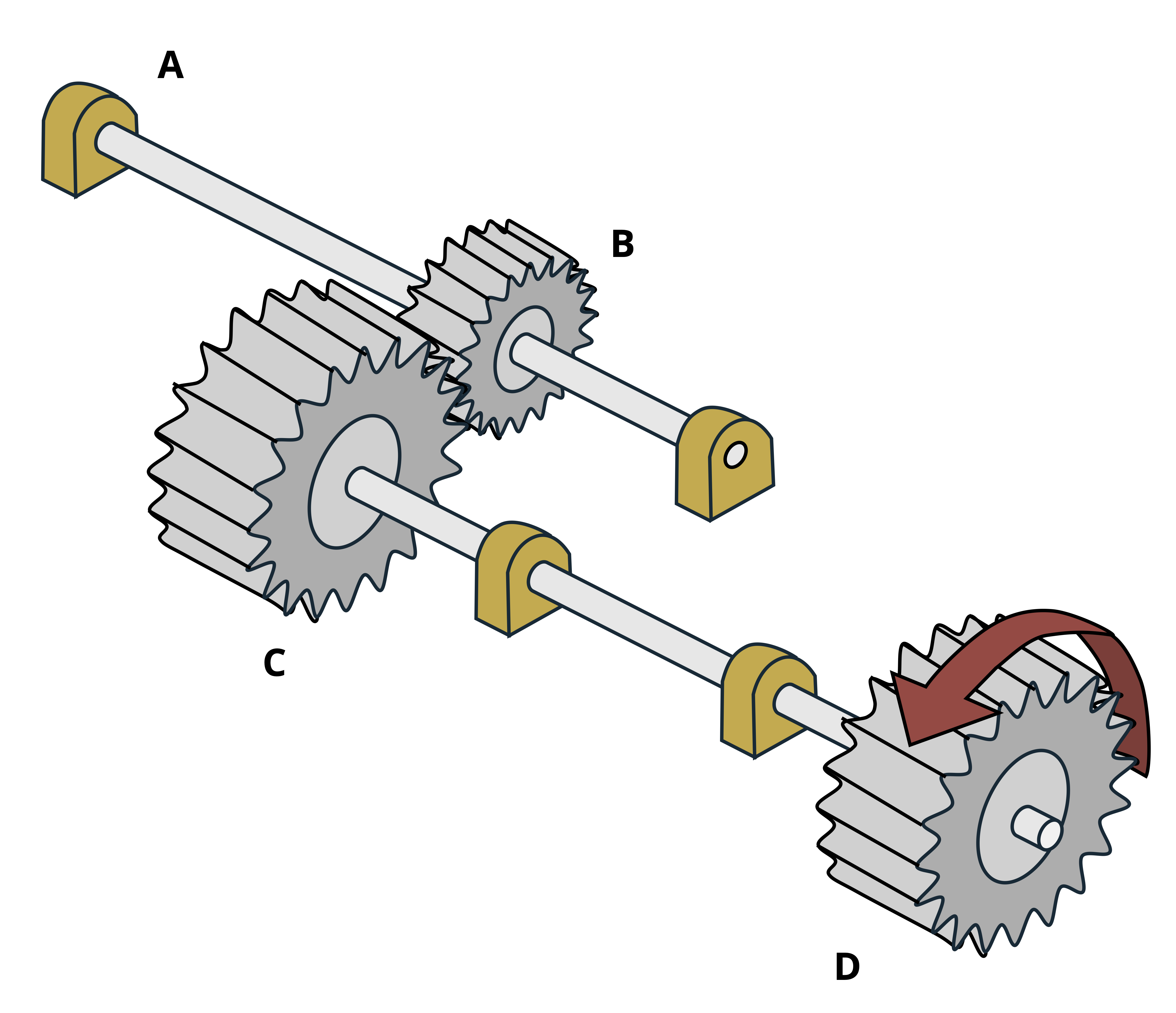

As mentioned in the introduction to torsion, one common application where we encounter circular shafts subjected to torsion is in power transmission shafts. In these types of assemblies, shafts are connected and apply torque to one another through gears and belts. If a shaft somewhere in the assembly is connected to a motor that causes it to rotate, that rotation is then transmitted to other connected shafts, which can in turn transmit rotation to even more shafts. Note that such systems are considered to be in equilibrium even with the rotation as long as the angular velocity remains constant.

Below is a brief derivation of the equation that relates torque to power, followed by a discussion of how torque and angle of twist are affected by the gear or belt connections between shafts.

6.6.1 Derivation of Power-Torque Relationship

Recall from other subjects of study that power is defined to be the time rate of change of work. The definition of work is force times distance. So power can be calculated as

\[ P=\frac{W}{t}=\frac{F \times d}{t}\text{.} \]

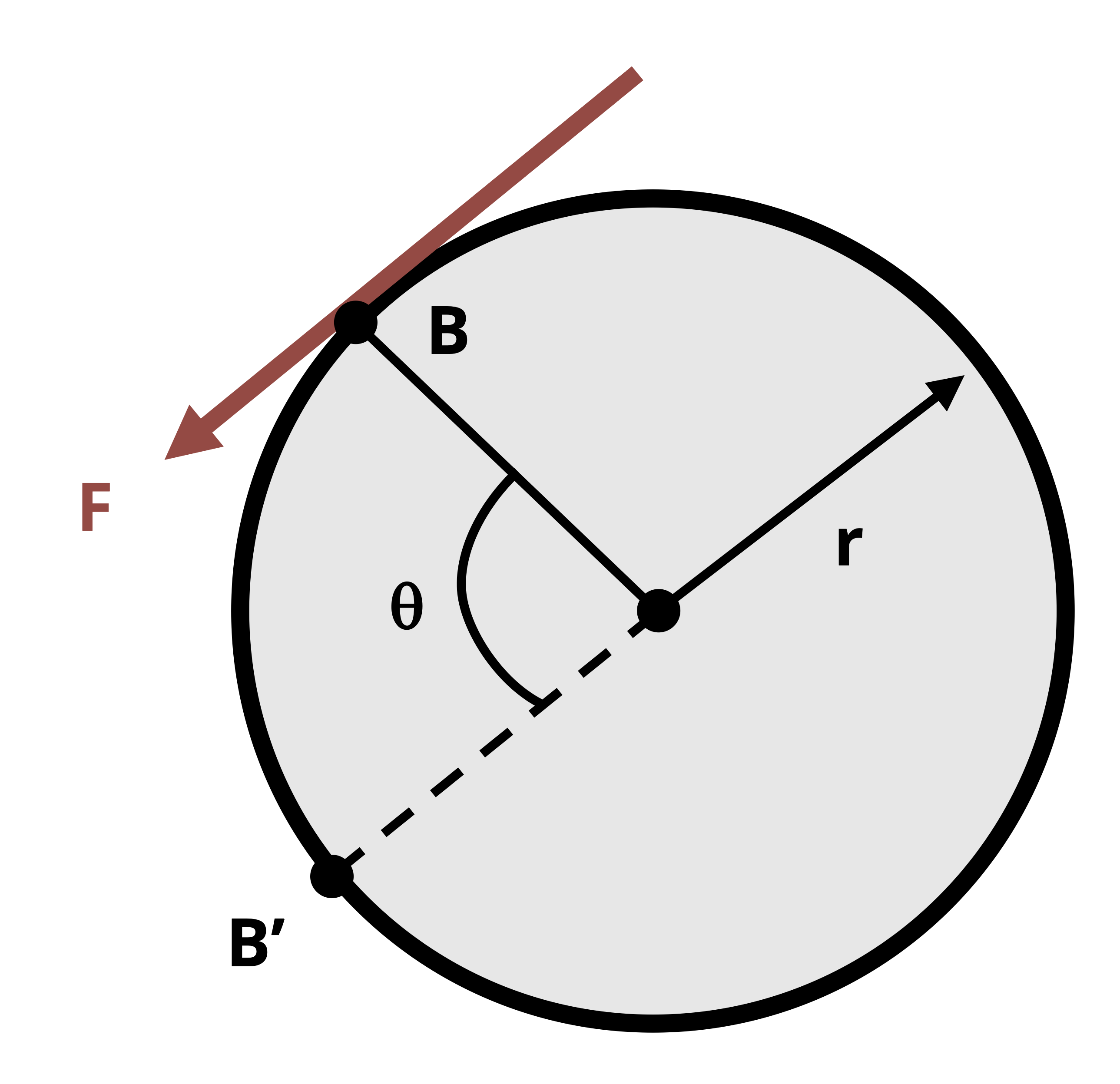

Within the context of rotating shafts, the force is applied to the shaft’s outer edge resulting in torque, and the distance is the arc length of a point on the shaft’s edge that travels around the circumference in a given amount of time, t. Figure 6.14 illustrates this point.

If the arc length over which point B travels is BB’ = rθ, then W = F(rθ). Since torque is equal to (F)(r), we can see that W = Tθ. Substituting this expression for work into the power equation above, we then have \(P=\frac{T \theta}{t}\). The \(\frac{\theta}{t}\) term is angular velocity, which is denoted here with the Greek letter ω. So the power equation can finally be expressed as

\[ \boxed{{P = T\omega}}\text{ ,} \tag{6.3}\]

P = Power [Watts, in.-lb/sec, horsepower]

T = Torque [N·m, lb·in.]

𝜔 = Angular velocity [rad/s, rad/sec]

6.6.2 Units

In SI the standard unit for power is the Watt (W), which is (N·m)/s. The N·m unit is also referred to as a Joule, so a Watt is a Joule/s.

In US customary units, power is commonly expressed as ft·lb/s or in.·lb/s. However, it is also common to express power in terms of horsepower, where 1 hp = 550 ft·lb/s. Note that there is a conversion difference between US horsepower and British horsepower. In this text, horsepower refers to the US version.

In applying Equation 6.3, the angular velocity ω must be expressed in radians per second. Sometimes angular velocity is given in Hz, where 1 Hz = 1 revolution/s. In this case, one must use the fact that 1 revolution = 2π radians to convert from Hz to rad/s. If angular velocity is given in revolutions per minute (rpm), then we must multiply by 2π radians and also divide by 60 to convert 1/min to 1/s. This reduces to an overall multiplication factor of π/30 to convert from rpm to rad/s.

A summary of the power related units and conversions is provided in Table 6.1 and Table 6.2.

Table 6.1: Power units

| SI (watt) | \[ W=\frac{N m}{s}=\frac{J}{s} \] |

| US | \[ \left(\frac{f t\ l b}{s}\right) \operatorname{or}\left(\frac{in.\ l b}{s}\right) \] |

| US (horsepower, hp) | \[ 1\ h p=\frac{550 f t\ l b}{s} \] |

| Hertz (Hz) | \[ 1\ H z=1 \frac{r e v}{s} \] |

| Angular velocity given Hz (rad/s) | \[ 1 \frac{rev}{sec}\ (2\pi \frac {rad}{rev})=\frac {2\pi \frac{rad}{s}}{Hz} \] |

| Angular velocity given rpm (rad/s) | \[ 1\frac{r e v}{\min }\left(\frac{2 \pi\ \mathrm{rad}}{1\ \mathrm{rev}}\right)\left(\frac{1 \mathrm{~min}}{60 \mathrm{~s}}\right)=\frac {\frac {\pi}{30}\frac {rad}{s}}{rpm} \] |

6.6.3 Torque Transfer Between Connected Gears (Gear Ratio)

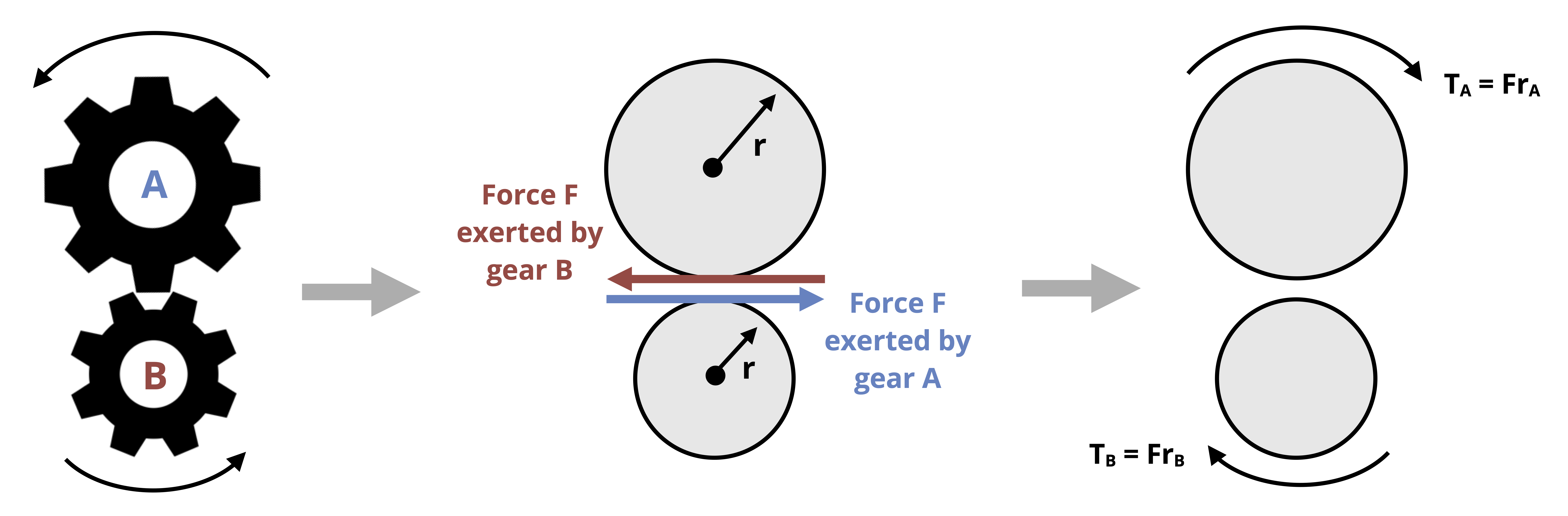

Consider two connected gears such as shown in Figure 6.15. The interaction of the teeth results in a force applied to each gear from one gear to the other. For equilibrium, this force must be equal in magnitude but opposite in direction. The force results in a torque that can be expressed as T = Fr.

Given that the force on each gear is equal in magnitude to the force on the other in equilibrium, we can write

\[ F=\frac{T_A}{r_A}=\frac{T_B}{r_B}\text{,} \]

which then allows us to express the torque exerted by one gear in terms of the torque exerted by the other as well as the ratio of radii.

\[ \boxed{{T_A=\frac{r_A}{r_B} T_B}} \tag{6.4}\]

The ratio of radii is known as the gear ratio. It can also be expressed as the ratio of gear diameters (\(\frac{d_A}{d_B})\) or the number of teeth on each gear (\(\frac{N_A}{N_B})\).

While the forces that result in torque are opposite in direction for each gear of the connected pair, the torques themselves are in the same direction. In Figure 6.15, the rightwards force gear A exerts on gear B results in a clockwise torque on gear B. Likewise, the leftward force gear B exerts on gear A results in a clockwise torque on gear A.

6.6.4 Angular Velocity Ratio of Connected Shafts

When two shafts are connected by a pair of gears, conservation of energy dictates that the power transferred into one shaft equals the power transferring out of the other (power in = power out, assuming losses are negligible).

For two connected gears A and B, if PA = TAωA and PB = TBωB and PA = PB, then \(\omega_A=\frac{T_B}{T_A} \omega_B\).

Substituting in Equation 6.4 gives us

\[ \boxed{{\omega_A=\frac{r_B}{r_A} \omega_B}}\text{ .} \tag{6.5}\]

Note that the gear ratio in this case is inverse of the one used to relate torques.

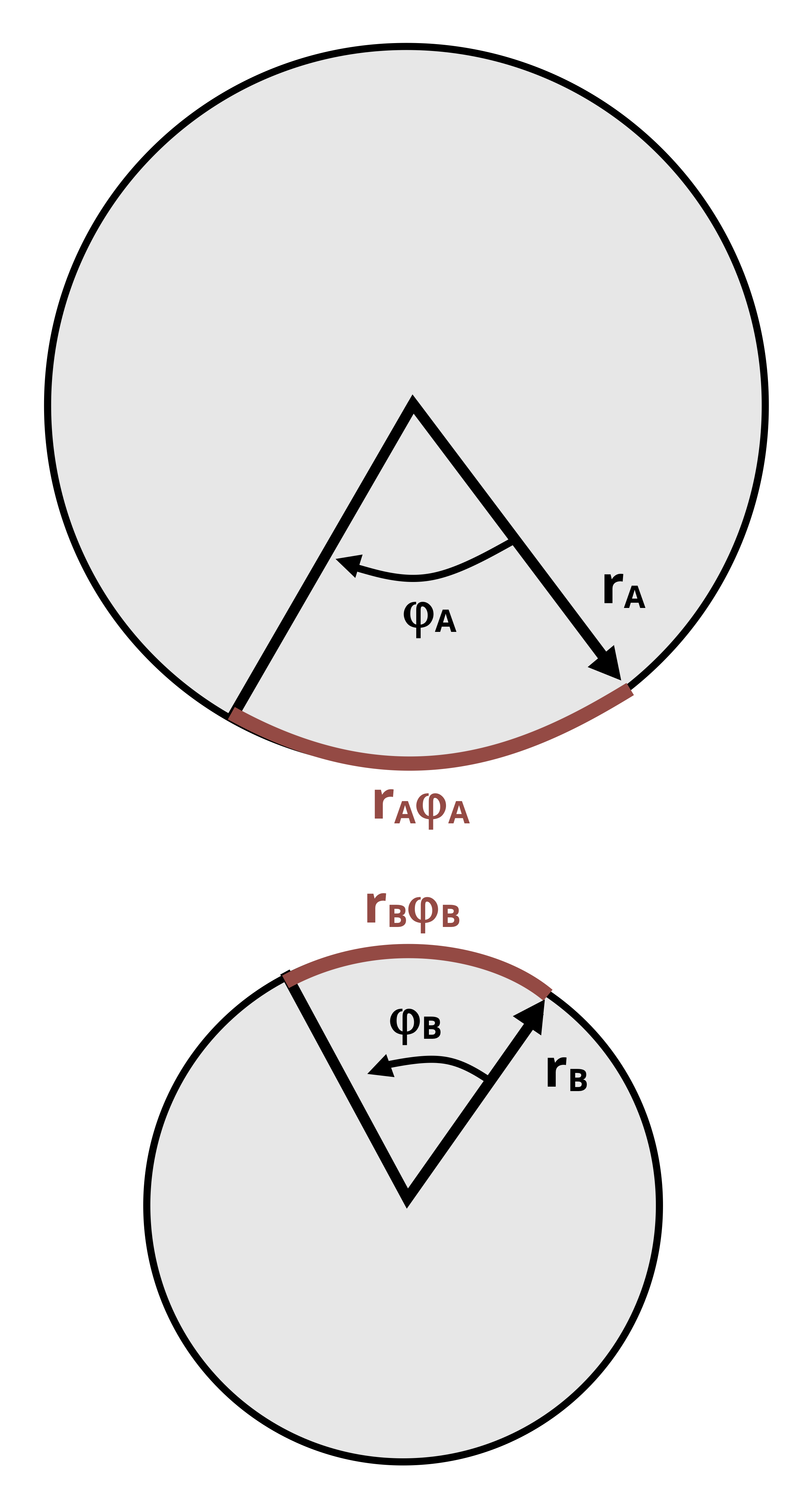

6.6.5 Angle of Twist

When two connected gears, each attached to a separate shaft, rotate they travel the same distance for a given amount of shaft rotation, or angle of twist. The distance of travel is equal to the arc length r·φ. Given that the gears exert forces in opposite directions (as illustrated in Figure 6.15), the direction of travel of each gear will also be opposite of the other, as depicted in Figure 6.16. For connected gears A and B, attached to shafts A and B respectively this can be expressed as

\[ {r_A\phi_A = -r_B\phi_B} \]

where φA is the angle of twist of shaft A and φB is the angle of twist of shaft B. Rearranging this relationship gives

\[ \boxed {\phi_A=-\frac{r_B}{r_A} \phi_B} \tag{6.6}\]

As with the angular velocities, the gear ratio is the inverse of that used to relate torques.

Example 6.7 presents a problem of power transmission with connected gears that utilizes the above concepts.

Summary

Click to expand

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

Figure 6.1: Horizontal wind blowing on the traffic lights will create a torsional moment in the vertical pole. James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.

Figure 6.2: Unloaded tube (left) and tube with torque applied (right). James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.

Figure 6.3: I-beam subjected to torsion unloaded (a) and with applied torque (b). James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.

Figure 6.4: Evidence of shear strain. James Lord. 2024. CC BY-NC-SA.